The Weight behind AI's Code

Part 6 of the "Beyond the Hype" Series

Small technical hiccup: this piece disappeared into the digital void briefly. Resending now, if you already read it, feel free to skip the duplicate. My apologies for the inbox clutter!

Continuing the workshop series...

We’ve covered Day 1 of the workshop. This included my session on African intelligence, Jason’s practical tech implementation guidance, Varaidzo’s landscape mapping, and Dr. Pholo’s AI Ladder framework. Each session built on the others, surfacing tensions between what AI systems can see and what they miss.

When people talk about AI, the conversation usually starts downstream with code, algorithms, and data governance. But there’s an entire upstream terrain that rarely gets attention, long before a single line of code exists. Yes, data centers shape the communities and environments around them, but the impacts stretch further back: extraction, sourcing, mining, logistics, and supply chains. Responsible AI begins there. It spans the full continuum, from the ground where minerals are pulled from the earth, to the server racks that host our models, to the algorithms that eventually reach users.

My Day 2 session shifted us firmly into that upstream space. We set aside epistemology and model design and instead asked a more elemental question: What is AI made of, and who pays the price for it? So I opened with the simplest provocation: What is Responsible AI?

The Responsible AI Landscape

There’s no shortage of answers. Tech companies like Microsoft, Google, and IBM frame Responsible AI around product development and user experience. Academic and policy communities emphasize governance and societal impact. Sector-specific approaches focus on industry risk and regulatory demands. Across all of these, familiar principles appear: fairness, transparency, accountability, privacy and security, safety and reliability, and human oversight.

I asked participants to review the landscape and note what stood out, what felt missing, what felt overemphasized, and what didn’t appear at all.

You can explore the landscape here as well.

These principles sound good and are necessary. But most Responsible AI conversations stay locked in the realm of digital ethics, algorithmic fairness, data privacy, and transparent decision-making. Important, yes, but they create a massive blind spot. They often ignore the material realities that make AI possible: supply chains, mineral extraction, the full hardware lifecycle from manufacturing to disposal, environmental damage, and the labor conditions of data workers. They overlook the perspectives of communities in the Global South who provide the raw materials yet have little say over the technologies built from them. They treat AI as if it’s weightless, pure code floating somewhere in the cloud. It isn’t.

When we interact with Claude or ChatGPT, we’re not merely accessing software. We’re tapping into a vast physical infrastructure. AI hardware is the machinery: chips, processors, and devices that gives these systems their computational force.

CPUs: general-purpose processors found in most computers.

GPUs: originally designed for gaming, now essential for the parallel processing AI requires.

TPUs: Google’s specialized chips built for machine learning workloads.

And an expanding ecosystem of accelerators optimized for highly specific tasks.

Those chips live inside servers and clusters, powerful machines stitched together to process and store staggering amounts of data. And all of this lives inside data centers: enormous, climate-controlled buildings housing thousands of machines running continuously. When we ask ChatGPT a question, the answer doesn’t come from our laptops. It comes from inside those data centers. Real places. Full of real machines. Consuming real energy, minerals, land, and labor.

The Geography of Control

So who controls all of this? Chip design is concentrated in a handful of companies, mostly in the U.S. (Intel, AMD, NVIDIA) and the UK (ARM, whose architecture powers most of the world’s smartphones). Actual fabrication happens primarily in Taiwan, led by TSMC, the world’s dominant manufacturer, followed by South Korea’s Samsung, with smaller capacities in the U.S. and China. The major data centers, the physical backbone of AI, are clustered in the U.S., Europe, and China. Africa, by comparison, hosts only a small number of large-scale facilities.

At present, Africa is not designing the chips. It is not fabricating them. It is not hosting the bulk of the computational infrastructure. Yet it holds a significant share of the minerals that make all of this possible.

A closer look at what these chips and servers are made of reveals the following:

Silicon forms the base of almost all chips, which come primarily from China, the USA, and Brazil.

Copper moves electricity inside chips and data centers; Chile and Peru are major sources, but also the DRC and Zambia.

Gold is used in chip connectors and comes from South Africa, Ghana, China, and Australia.

Aluminum for casings and cooling comes from Australia, Guinea, and China.

There are more specialized materials. Rare earth elements for magnets, hard drives, and cooling fans are mostly from China, but also Myanmar and Burundi.

Nickel and lithium for batteries.

And two minerals that are absolutely critical: cobalt and coltan. Cobalt powers the rechargeable batteries in every laptop, every phone, every device running AI at the edge. The DRC produces over 70% of the world’s cobalt. Coltan gets refined into tantalum, which is essential for the capacitors that make chips stable and heat-resistant. The DRC holds 60% of global coltan reserves.

Without these minerals, AI hardware as we know it cannot exist.

A Story From the DRC

Let’s focus on what this actually means on the ground. Right now, an estimated 40,000 children are mining cobalt and coltan in the DRC. Some are as young as six. Many work 10–12 hour a day, without protective equipment, earning less than $2 a day. These are the children extracting the minerals that power our smartphones, our laptops, the servers running ChatGPT, the models predicting climate shocks, the tools evaluating development programs, the very technologies we frame as progress.

The environmental costs track alongside the human ones. Producing a single kilogram of cobalt emits 15–20 kilograms of CO₂. Artisanal mining destabilizes soil structures and pollutes local water sources. Coltan extraction in the Kivu region has driven deforestation, biodiversity loss, and long-term land degradation. And when the hardware becomes obsolete after two or three years, much of it returns to the continent as toxic e-waste. The cycle begins and ends in extraction.

The DRC holds the minerals. But it does not control the value that emerges from them. Mining concessions are typically owned or leased by foreign corporations. Manufacturing is concentrated in Asia. The intellectual property sits in the U.S. and Europe. The data centers belong to a handful of global tech firms. The DRC provides the raw materials (the foundation), and yet the wealth, power, and governance flow elsewhere.

Here’s a scenario I can’t stop thinking about:

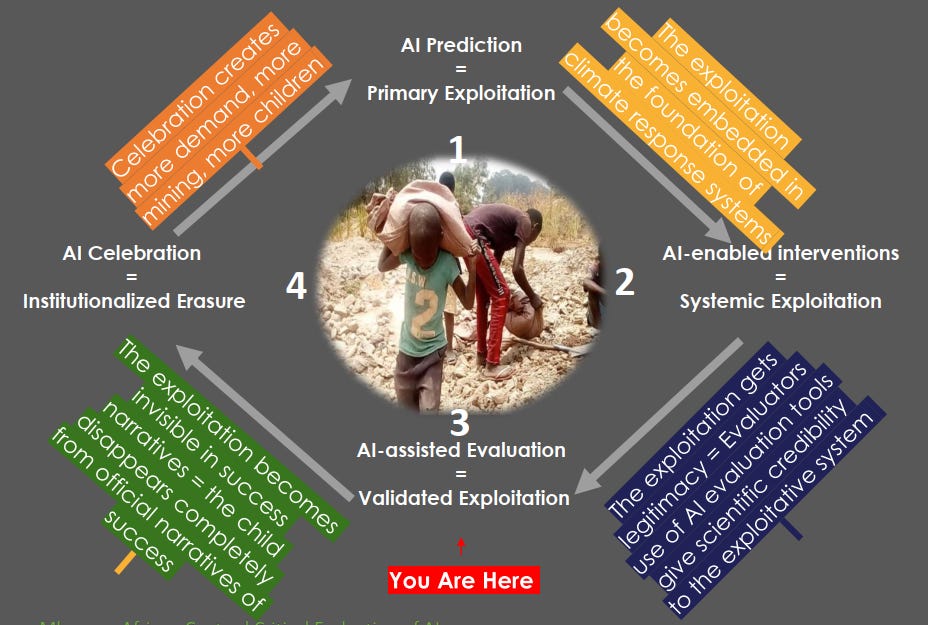

Somewhere in the DRC, a child is mining cobalt today. That cobalt will eventually sit inside an AI model predicting tomorrow’s drought in Kenya. That prediction will shape a climate intervention. That intervention will later be evaluated using AI-powered monitoring tools. And all three (the prediction, the intervention, the evaluation) will be celebrated as “climate innovation” at the next global AI summit on Africa. The child powers every layer of that cycle. And yet the child disappears from the story entirely.

If we trace this more explicitly, we’ll see that the AI prediction depends on primary exploitation, minerals extracted under conditions I just described, powering the infrastructure that makes predictions possible. Those predictions inform AI-enabled interventions, which require more AI tools, which require more minerals. The cycle deepens. Then comes AI-assisted evaluation, where evaluators use tools dependent on the same extraction to assess impact. The evaluation legitimizes the system without questioning its foundation. Finally, we get to AI celebration, the success stories, the innovation narratives, the awards, and summits. The supply chain becomes invisible.

The child miner disappears.

The Blind Spot in Evaluation

This is why I’m talking about it in a workshop on AI in monitoring, evaluation, research, and learning. Evaluation is fundamentally about assessing impact. We measure whether programs work, whether interventions achieve their goals, and whether resources are being used effectively. We’ve built increasingly sophisticated methods for this. We can trace program theories, identify unintended consequences, and assess long-term sustainability. But we don’t apply that same rigor to our tools.

When evaluators use AI-powered data collection platforms, AI-assisted analysis tools, AI-driven dashboards, we assess the programs, but not the systems we’re using to do that assessment. We have a blind spot and it’s enormous. To be fair, this is not just happening in evaluation. Development programs, climate initiatives, health interventions, all increasingly rely on AI tools. All celebrate “digital transformation” and “innovation.” Almost none ask: What is this innovation made of? Who paid for this transformation?

This matters because these resource demands fuel human rights violations. Artisanal mining with child labor. Workers without protective equipment. Exploitative wages. Conflict financing through mineral sales to armed groups. And complete invisibility in narratives about “smart AI” and “cutting-edge technology.” They fuel ecological degradation, deforestation, and land degradation. Water pollution poisoning communities. Carbon emissions from transporting minerals from the DRC to refineries, often in China, then to manufacturers in Taiwan or South Korea and they create new dependencies. African countries need computing infrastructure, which requires massive energy investment. Technical expertise leading to brain drain as skilled workers leave for better opportunities elsewhere. Data sovereignty becomes difficult when we don’t control the infrastructure. And there’s economic dependency, extracting minerals, selling them cheaply, then buying back the finished technology at premium prices.

When we think about that structure, we see that Africa provides the foundation, and then pay to access what was built on it.

What’s Being Done

There are efforts to address these issues. The OECD and ILO provide guidelines for supply chain transparency. Initiatives like the Responsible Minerals Initiative are piloting blockchain and AI tools to trace supply chains (Yes, using AI to trace the problems AI causes, the irony isn’t lost on me). Lawsuits against major tech firms for alleged complicity in DRC child labor have brought some attention. The EU AI Act and GDPR mandate stricter oversight of supply chain ethics.

These efforts matter. But they’re not sufficient yet because they operate within the same extractive paradigm. They try to make extraction more ethical, more traceable, more compliant, often without questioning whether the fundamental structure needs rethinking. And critically, the evaluation field hasn’t systematically embedded these considerations into standard practice. We evaluate programs but we don’t evaluate the tools we use to evaluate.

This is where Made in Africa Evaluation(MAE) becomes relevant. MAE has been pushing for evaluation practices rooted in African contexts, values, and knowledge systems. It exposes power relations behind who funds, controls, and benefits from programs. It prioritizes community voices and local accountability and provides crucial philosophical grounding.

But MAE wasn’t designed with AI-specific challenges in mind. It doesn’t yet fully address data governance in AI systems, algorithmic opacity and bias, global tech dependency, or supply chain ethics. And it doesn’t differentiate between evaluating AI-powered projects (like an AI-driven health app), evaluating AI-focused initiatives (like AI policy or training programs), and AI-powered evaluation (using AI tools in evaluation practice itself). These require different approaches, different questions, different frameworks.

What do I propose?

So I proposed to workshop participants that we need something new: an African-Centred Critical Evaluation of AI framework. Not as the final answer but as a starting point, a first draft. Something that expands MAE into AI-specific domains while ensuring Africa sets its own evaluation standards in the AI era.

Why do I think a distinct framework is essential? Because most evaluations still use OECD/DAC frameworks created for donor accountability, not African agency. Because imported AI “ethics” models risk digital recolonization, Africa judged by others’ standards again. Because without an African framework, AI evaluations can erase local knowledge and reproduce dependencies. Because evaluators risk becoming enforcers of external agendas instead of agents of African priorities. And because AI is advancing faster than policy or evaluation practice. If the African evaluation community doesn’t define boundaries, principles, and structures now, extractive models will become the default before we’ve had a chance to shape alternatives.

The Framework I’m Working On: I proposed five pillars. Each has acknowledged challenges and potential ways to address them.

First, context-specific assessment. Start with African realities rather than importing solutions. The challenge is that it’s hard to adapt frameworks across diverse African contexts. The mitigation might be using rapid contextual scans, engaging local stakeholders, and iteratively adapting evaluation tools.

Second, power and dependency analysis. Examine who controls data, algorithms, and outcomes. Identify dependencies that may reproduce inequities. The challenge is that power dynamics are often opaque, and some stakeholders may resist scrutiny. We might address this through participatory mapping of actors, triangulated data sources, and ethical transparency.

Third, knowledge systems integration. Integrate local knowledge alongside technical evidence. Respect and amplify African epistemologies. The challenge is that local knowledge is often undervalued or difficult to operationalize. We might address this by co-designing evaluation methods with communities, documenting local epistemologies, and combining qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Fourth, bottom-up action. Empower communities and evaluators to set standards, define success, and influence evaluation decisions. The challenge is that communities may lack capacity to influence evaluation design fully. We might address this through facilitation and training, structured feedback mechanisms, and iterative review cycles.

Fifth, upstream impact tracing. Follow the full chain of AI projects, from material sourcing to social outcomes. Assess both upstream and downstream impacts. The challenge is that following the full chain from resource extraction through technology to social outcomes is complex and resource-intensive. We might focus on critical checkpoints, use proxy indicators where direct data is unavailable, and highlight gaps for transparency rather than claiming complete coverage.

This last pillar is the one that would force us to ask: Where did the tools I’m using come from? What was their supply chain? Who paid the price for this evaluation infrastructure?

I’m not claiming to have figured this out. The framework is a first draft, meant to start conversations rather than end them. What I do know is that we can’t step outside these extractive systems entirely. The laptop I’m typing on, the phone you might be reading this on, the servers hosting this article, all depend on the same supply chains I’ve been describing. But we can choose how we participate. We can move from unconscious reproduction of harm to deliberate interrogation of our tools and practices.

You can access the framework here.

We can start asking the difficult questions: What is this AI tool made of? Who extracted the minerals that power it? What were their working conditions? What environmental damage occurred? Who profits from this supply chain? Who is erased from the narrative?

What I’m Asking

The framework I presented is not final; I need help refining it. Whether you work in evaluation, development, technology, or you’re just someone thinking about these questions, you can get involved and help figure out:

What do you think is missing?

Are these pillars relevant?

Are the mitigation strategies feasible?

What additional considerations are needed for evaluating AI-powered projects versus AI-focused initiatives versus AI-powered evaluation itself?

What would you add about supply chain ethics in evaluation practice?

How do we trace upstream impacts practically?

What does responsibility mean in your context?

How do we balance the urgent need for AI tools with the urgent harm they’re causing?

I don’t have all the answers. But I know we need to start asking these questions.

If our evaluation frameworks can’t see the 40,000 children mining the minerals powering the AI revolution; if they can’t trace the connection between that labor and the tools we celebrate; if they can’t hold the entire system accountable, then what, in truth, are we evaluating?

What’s your reaction to this? Does the evaluation field have a responsibility to assess the tools it uses, not just the programs it evaluates? What would change if we took upstream impact seriously?

I’m looking for feedback on the framework. You can provide feedback here

Next week: Varaidzo Matimba on African Perspectives on Tech Justice, including Afrofeminist approaches and decolonial frameworks for AI.

Thank you for reading!

Support this work

This work exists to break down complexity in tech and amplify African innovation for global audiences. Your support keeps it independent and community-rooted.

Your support is appreciated!

Rebecca, as always, you’ve cut straight to the structural heart of the problem. Your framework doesn't just add an African perspective—it recenters the entire AI ethics debate on material justice and historical continuity. Reading it, I kept thinking: You’ve provided a map. Nowthe tools are needed navigate the territory.

This is where I find myself wrestling with the next layer of strategy. Because the system you’re critiquing operates on a different logic—what we might call the "social media playbook": hype, scandal, performative repair (an ethics board, a transparency tool), and full-speed acceleration. Moral appeals alone get filed under "ESG," managed by PR.

Your five pillars are the blueprint for a just system. The urgent question now is: How to use them as levers within the unjust system we actually have?

I’m reminded of the parallel fight at the UN climate summits—the push by African and vulnerable nations for a "Loss and Damage" fund. The argument there is the similar: You built your wealth on a process that externalized costs onto us; this is not charity, it’s a liability. It’s the right argument. And yet, it stalls against the wall of power, reduced to negotiated aid, not accepted debt.

The difference with AI’s mineral foundation—and potential leverage—is more immediate. Here, the "cost" isn't a diffuse carbon blanket; it’s a physical choke point. The DRC holds ~70% of the world's cobalt. No cobalt, no industrial-scale AI.

So what if you took Pillar 5 (Upstream Impact Tracing) and fused it with that material reality? What if the goal isn’t just to trace, but to use tracing to re-price the mineral itself?

From: "Your AI is unethical because it uses cobalt mined by children."

To: "The 'True Cost' of your training cluster's cobalt includes $X for community health, $Y for ecosystem remediation, and $Z for child rehabilitation. This is an unpaid liability. You can either partner with us to build a clean, traceable supply chain at this new cost, or explain to your shareholders why you chose the cheaper, toxic alternative."

This turns your pillar from a diagnostic tool into a negotiating instrument. It shifts the fight from summits (where they plead) to boardrooms and supply contracts (where they set terms).

In this light, each pillar could be operationalized as a form of strategic friction:

Pillar 2 (Power Analysis) becomes exploiting the rift between Western "ethical branding" and Chinese "infrastructure-for-resources" deals to mandate local processing plants.

Pillar 4 (Bottom-Up Action) becomes organizing artisanal miners into a union that doesn’t just demand better wages, but withholds the "social license" required for a clean ESG audit.

The vision your framework provides is non-negotiable. The brutal next question is one of tactics: How do you move from mapping the ethical high ground to holding the strategic high ground—using the very minerals, data, and scrutiny that the system cannot function without?

You've clearly lit the up the path. The next phase is building the roadblocks.