Offline Doesn't Mean Unintelligent

Rethinking fundamental assumptions about intelligence in the digital age

We’ve come to mistake internet access for access to knowledge and, dangerously, as a stand-in for intelligence itself. This subtle yet pervasive assumption has profoundly shaped public perception, international development agendas, educational frameworks, and hiring practices across the global technology landscape. From Silicon Valley boardrooms to rural classrooms, we've internalized a dangerous equation: connectivity equals capability.

But this equation, this reflexive correlation between digital access and intellectual capacity is not merely flawed. It is fundamentally exclusionary, ethically problematic, and intellectually dishonest. Being offline does not imply a lack of intelligence or potential, it more accurately reflects systemic inequality in infrastructure, opportunity, and digital access. This distinction is not semantic; it strikes at the heart of how we conceptualize human capability in the 21st century.

The Infrastructure Illusion

Globally, over 2.6 billion people remain offline, according to the International Telecommunication Union's 2023 report on digital development. This staggering number representing nearly one-third of humanity is not randomly distributed. The vast majority live in low- and middle-income countries, where digital infrastructure is either underdeveloped, unreliable, prohibitively expensive, or entirely absent.

The architecture of this disconnection follows familiar patterns of global inequality. According to the GSMA’s 2024 State of Mobile Internet Connectivity report, only about 27% of the total population in sub-Saharan Africa uses mobile internet services, though this rises to 46% among adults.

The student in the DRC studying by kerosene lamp, the urban informal worker in Zimbabwe without disposable income for data plans, the indigenous elder in rural Tanzania maintaining traditional knowledge systems all possess cognitive capacities, problem-solving abilities, and creative potential equivalent to their connected counterparts. Their disconnection stems not from intellectual limitations but from systemic factors entirely beyond individual control.

These disparities are not natural phenomena but the result of specific historical, economic, and political factors. Colonial infrastructure patterns prioritized extraction over comprehensive development. Privatization of telecommunications has incentivized coverage of profitable markets while neglecting others. Regulatory frameworks have often failed to ensure universal service obligations are met.

To assume otherwise, to conflate exposure to digital tools with innate intellectual capability, is to mistake privilege for potential. This conflation doesn't just misdiagnose the problem; it fundamentally misdirects the solutions.

Visibility ≠ Value

The proliferation of digital platforms has created a fundamentally skewed meritocracy where visibility has become dangerously conflated with value. Those with consistent online presence, particularly on professional platforms like LinkedIn, code repositories like GitHub, publishing platforms like Substack, or social media ecosystems like X, accrue a form of intellectual credibility that often goes unexamined and unchallenged.

This visibility bias operates through multiple mechanisms. First, the algorithmic infrastructure of these platforms privileges certain forms of participation and expression over others, creating what scholar Safiya Noble terms "algorithmic oppression." Second, the time-intensive nature of maintaining a digital presence favors those with stable internet access, and cultural familiarity with platform norms, all markers of socioeconomic privilege rather than intellectual capacity.

The resulting dynamic creates a pernicious feedback loop:

…those who are visible in digital spaces are presumed knowledgeable by virtue of presence alone, while those who are absent, regardless of reason, are rendered intellectually invisible. Their absence becomes misinterpreted as intellectual deficiency rather than infrastructural exclusion.

In a case of two hypothetical knowledge workers: one with reliable high-speed internet who regularly publishes thought pieces on industry forums, and another with intermittent connectivity who concentrates their limited online time on essential communications. The former accumulates social and professional capital through digital visibility, while the latter potentially possessing equal or superior insight remains unseen and thus unconsidered.

Research on social media screening shows that hiring managers in global technology firms consistently rate candidates with robust digital footprints more favorably than those with minimal online presence, even when presented with identical qualifications. This preference persist even when hiring managers are aware of digital access disparities in candidates' regions of origin.

This systematic privileging of the digitally visible doesn't merely disadvantage talented individuals, it fundamentally constrains the collective intelligence available to address the most pressing challenges. When we draw primarily from digitally represented knowledge pools, we miss the vast reservoirs of insight, perspective, and problem-solving approaches from communities underrepresented online.

Intelligence Is Contextual

The dominant paradigm of intelligence in contemporary discourse is neither universal nor neutral; it is historically situated, culturally specific, and increasingly digitally mediated. Standard definitions and measurements of intelligence have emerged primarily from Western psychological traditions, privileging particular cognitive skills (abstract reasoning, rapid information processing, text-based literacy) while marginalizing others (ecological knowledge, embodied skill, oral tradition, social intelligence).

This narrowed conception of intelligence has become further constricted through its increasing association with digital fluency and computational thinking. The scholar Ruha Benjamin describes this as "the new Jim Code", ostensibly neutral technological systems that encode and reproduce existing social hierarchies under the guise of objectivity.

Yet cognitive science, anthropology, and cross-cultural psychology have repeatedly demonstrated that intelligence manifests in profoundly different ways across cultural contexts. Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences identifies at least eight distinct forms of intelligence, including spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, and naturalistic intelligences, many of which find limited expression in conventional digital environments.

In communities worldwide, sophisticated knowledge systems operate through non-digital channels:

In the Caroline Islands of Micronesia, traditional navigators can sail thousands of ocean miles without instruments, using a complex mental model of star positions, wave patterns, and marine life behavior. Research has documented how these navigators internalize star compasses with up to 32 reference points, a feat of spatial intelligence rarely captured by conventional intelligence metrics.

The Sámi people of northern Scandinavia maintain a specialized vocabulary of over 300 terms to describe snow conditions, an intricate taxonomic system that enables precise environmental assessment crucial for reindeer herding. As documented by Magga (2006), this linguistic-ecological knowledge system encodes generations of observational data more nuanced than many digital weather prediction tools.

Silvanos Chirume’s study reveals that the Shona people of Shurugwi County possess rich, culturally embedded mathematical knowledge applied in daily life and community problem-solving. This knowledge system is practical, oral, and symbolic, differing significantly from Western formal mathematics but equally valid and valuable.

Farmers and pastoralists in East Arica use a combination of meteorological, biological, and astrological indicators such as wind direction and strength, star-moon alignments, cloud types, lightning, thunder, sky color, and rainbow appearances to forecast rainfall and seasonal changes. These indicators have been passed down through generations and are trusted sources of information for local communities.

These knowledge systems represent sophisticated forms of intelligence, pattern recognition, data interpretation, predictive modeling, and information transfer that have evolved to address specific ecological and social challenges. They often operate through non-textual, non-digital modalities: oral tradition, apprenticeship, embodied practice, and direct environmental engagement.

This is not to romanticize non-digital knowledge or suggest technological advancement is undesirable. Rather, it is to recognize that intelligence exists along multiple axes, and digital expression represents just one dimension among many. When we collapse intelligence into digital performance, we commit both an epistemological error (misunderstanding what intelligence is) and an ethical one (devaluing the knowledge systems of billions).

The Cost of Digital Bias

The assumption that intelligence correlates with digital participation extends far beyond individual perception, it has become structurally embedded in systems that allocate resources, opportunities, and intellectual authority. This embedding creates cascading effects that perpetuate and amplify existing inequalities.

In development financing, initiatives promoting "digital solutions" often receive disproportionate funding compared to approaches addressing foundational needs that might create more sustainable impact. Digital development projects often reach primarily urban, relatively affluent populations that already had basic digital access, effectively bypassing the most vulnerable communities.

Educational systems increasingly emphasize STEM and computational skills, often at the expense of cultural knowledge, creative expression, and place-based learning, particularly in regions deemed "developing." This curricular prioritization implicitly devalues indigenous knowledge systems and local expertise, creating epistemic extraction, the replacement of contextually-relevant knowledge with standardized digital frameworks.

This inclination towards technological solutions is also reflected in research funding and scholarly attention. For instance, analyses of innovation research across the African continent have indicated a strong predisposition towards technological interventions, with non-digital innovations often receiving less examination, despite their proven importance in tackling local challenges.

Beyond questions of access and visibility lies a more fundamental issue: who possesses the authority to generate knowledge, define research priorities, and claim ownership of intellectual contributions. Nowhere is this gap more evident than in the African research landscape, where colonial patterns of knowledge extraction persist in modern forms. The consequences extend beyond academic politics. When research priorities are determined primarily by external funders, they often misalign with local needs. Research in many low-income contexts frequently shows that funding doesn't always match the most pressing local health needs. Instead of focusing on prevalent issues like maternal health or common infections, a significant portion of investment often goes to global health priorities that attract more external donor interest.

This pattern, often characterized as "parachute science" where researchers from well-resourced nations collect data in lower-resource settings without building sustainable local research capacity, represents a subtle but pervasive neo-colonial dynamic in global knowledge production. It reinforces the assumption that expertise resides primarily in well-resourced, digitally-connected institutions rather than in communities with deep contextual understanding. The intelligence ownership gap thus constitutes more than a mere disparity in research output. It represents a fundamental power imbalance in who defines which problems deserve investigation, which methods are considered rigorous, which knowledge is deemed legitimate, and ultimately, who benefits from the solutions developed.

Even algorithmic development incorporates these biases. Machine learning systems trained primarily on data from digitally-active populations develop skewed representations of human knowledge, preference, and behavior. When deployed globally, these systems further marginalize already-underrepresented perspectives. As AI researcher Timnit Gebru notes, these systems effectively "launder human bias through mathematics," presenting algorithmic outputs as objective when they actually reflect and amplify existing digital divides.

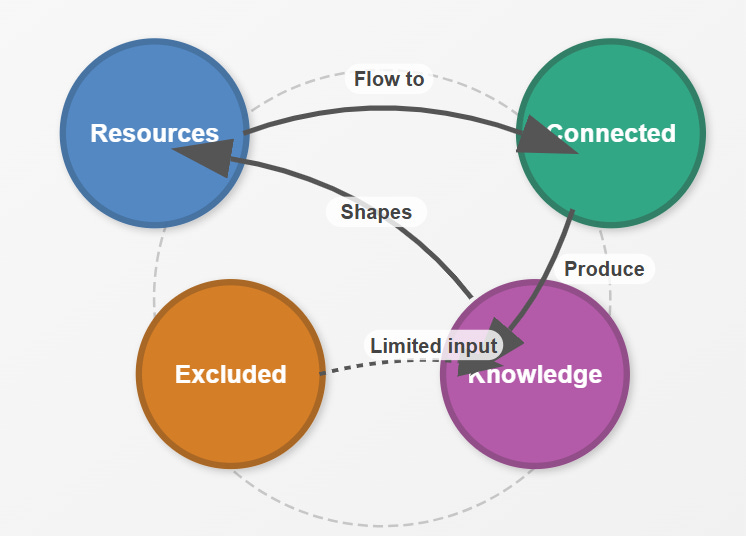

These structural biases create a self-reinforcing cycle: resources flow disproportionately to the already-connected, who then produce digital knowledge that further shapes resource allocation decisions.

Meanwhile, communities with limited digital representation find themselves systematically excluded not just from digital participation but from the broader knowledge economy. Left unchallenged, this self-reinforcing bias perpetuates what appears to be digital meritocracy but functions as digital elitism masked as innovation.

Beyond bandwidth

Addressing these interlinked challenges requires more than incremental policy adjustments or technological fixes. It demands a fundamental reconceptualization of the relationship between technology, knowledge, and human capability. Such a reimagining begins with decoupling our assessment of intelligence from digital participation, recognizing cognitive capacity as independent from technological access.

Human intelligence encompasses far more than digital performance, and that technological development should enhance rather than replace the diverse knowledge systems humans have developed across cultural contexts. Pursuing a more inclusive tech ethic requires unlearning the unconscious assumption that brilliance only speaks in bandwidth, that cognitive capability can be measured by digital presence or technological adoption. It means recognizing that the rural farmer forecasting weather through environmental observation, the oral historian preserving community memory, and the artisan encoding mathematical patterns in textiles are engaging in forms of intelligence that deserve not just acknowledgment but celebration and incorporation into our collective knowledge commons.

Conclusion

In our collective rush toward digital transformation, we have inadvertently constructed a dangerously narrow conception of human capability, one that privileges particular forms of technological engagement over the vast spectrum of human intelligence. This reflexive equation of digital connectivity with intellectual potential represents not just a conceptual error but an ethical failure with profound implications for how we distribute resources, recognize knowledge, and design our collective future.

The picture painted here, from infrastructure disparities and visibility biases to contextual intelligence and knowledge ownership gaps, points to an urgent need to disentangle our assessment of human capability from digital participation. Digital connectivity remains vitally important for expanding human opportunity, but we must recognize it as an infrastructure challenge rather than an intelligence metric.

When we mistake the absence of connectivity for the absence of capability, we engage in a form of technological determinism that both misdiagnoses the problem and misdirects our solutions. We invest in "bridging the digital divide" without addressing the underlying social, economic, and political factors that created that divide. We build technologies that serve the already-connected while overlooking the knowledge and needs of billions beyond the reach of reliable connectivity.

More fundamentally, by conflating digital performance with intelligence itself, we risk diminishing the rich diversity of human cognitive approaches that have enabled our species to thrive across vastly different ecological and social contexts. We implicitly devalue the sophisticated knowledge systems, oral traditions, embodied practices, observational sciences, and community-based problem-solving approaches that operate through non-digital channels but nonetheless represent profound intellectual achievement.

A more inclusive approach requires holding two truths simultaneously:

1)digital connectivity represents a vital infrastructure need that should be universally available, and 2)human intelligence exists independently from technological access.

Our frameworks for recognizing, developing, and valuing human capability must accommodate both digital and non-digital expressions of intelligence. As we continue building our increasingly digitized world, we must resist the temptation to see technological participation as a proxy for human potential. Offline doesn't mean unintelligent. It often means systematically excluded from the infrastructure, visibility, and authority structures that dominate our digital age. And unless we directly challenge this conflation of connectivity with capability, we risk building a future that merely digitizes existing inequalities rather than transcending them, a future that reflects the biases of the present rather than the full spectrum of human intelligence and creativity that exists across connected and unconnected spaces alike.

The real question isn’t whether the unconnected deserve to be connected, it’s whether those of us who are connected have the right to define intelligence, knowledge, and progress for everyone else. How we respond to this will shape whether digital transformation drives broader human flourishing or simply deepens existing hierarchies of privilege and power.

This newsletter is independently researched, community-rooted, and crafted with care. If you or your company believe in amplifying underrepresented voices in tech, AI, and data, consider becoming a sponsor or partner.

Let’s signal what matters together.

📩 Get in touch at reambaya@outlook.com

or…